Why You Continue to Deny Cyclical History

A Reconciliation Between Linear and Cyclical History

If you prefer the audio of this article, click here.

Cyclical history enjoys a fair bit of currency in the radical right, but still it’s a contentious topic. Some people hold to cyclical history religiously. Some to linear history. Is it possible to reconcile the two? In this article we will do just that. But first, let’s examine the reasons why cyclical history is a dividing point within the radical right.

The first reason is the religious divide between paganism and Christianity. Jewish and Christian theology require a linear view of history. In Judaism, the story goes like this: the Jewish people fall from grace but are redeemed by Yahweh, culminating in a cataclysmic battle which rescues them from exile, returns them to Israel, converts the Goyim to the worship of Yahweh, and ultimately culminates in a final judgment and a resurrection of the Jews in the world to come. In the case of Christianity, we move from the Jewish religion in its unfulfilled state to the coming of the Jewish Messiah who redeems all humanity, to a time of tribulation, a second coming of the Messiah, the resurrection of the dead, and the final Armageddon. In Jewish and Christian eschatology, there are several one-time, irreversible events that move history toward a definite goal. In pagan theologies, history is almost invariably cyclical. While Jewish and Christian theology may accept a qualified cyclicity within history, the cycles rather resemble a helix, moving periodically but ultimately in one direction.

The second reason why cyclical history is not unanimously accepted in the radical right is that it tends to downplay human agency in the world. Marxism, with its acceptance of the “trends and forces” theory of history, virtually rejects human agency, making this agency the result of material conditions. The major alternative to this view is the Great Man theory of history propounded most famously by Carlyle,1 where the great man is sent “as lightning out of Heaven, that shall kindle the world”. This fits much better than trends and forces theory with a right-wing worldview.2 Cyclical history suggests a kind of fatalism which doesn’t sit comfortably with the idea of a great man who forges history according to his own will, and it also feels like too much of a blackpill in an age where things are clearly falling apart.

But is there a way that cyclical history can be reconciled with linear history? Surely when we look at history we see some things that are linear. We see an overall moral decline. We see an overall material progress. These are not just illusions, but very real. At the same time, we also see the rise and fall of empires, peoples, ideas, and even something so mundane as fashion. How can both be valid? Can they both be valid?

In answering this question, the first thing to note is that there is not one cycle. We have written quite a bit here about the various cycles of history. We have:

The monogamy vs. polygamy cycle;

the Strauss-Howe cycle;

the cycle of ethnic synthesis vs. fracturing identified by Hearn and others;

the threat detection/religiosity vs. threat blindness/irreligiosity cycle;

the Spenglerian cycle;

the cycle of complexity and collapse identified by Tainter;

the ancient cycle of barbarism vs. civilization as embodied in the Tale of Sinuhe;

Polybius’ Anacyclosis;

the cycle of Asabiyyah identified by ibn Khaldun;

Vico’s cycle

And these are just the cycles that we have discussed at length here. Apart from these ten, there are probably at least a dozen more, some of which Neema Parvini has detailed in his book Prophets of Doom.3 All of these have, if not monocausal explanatory power, at least a very large grain of truth to them.

The first step toward understanding how cyclical and linear history can both be valid is to notice just how many cycles there are. In fact, you may have already guessed where this is going.

When you get multiple periodic factors all interacting, this often produces an effect that appears to be linear or chaotic, but is really at bottom cyclical. Take as a simple example the tires on your car. Each of these tires may wear at different speeds depending how you drive, and you might have three new tires and one old tire. Each tire may have a slightly different diameter and a slight wobble, a periodic movement. If the wobbles from each tire are out of sync but combine in a particular way, the car might start drifting in one direction—producing a small, steady pull to the side. This pull is the result of the sum of all the individual cyclical wobbles. What seems like a linear drift is really driven by underlying cycles.

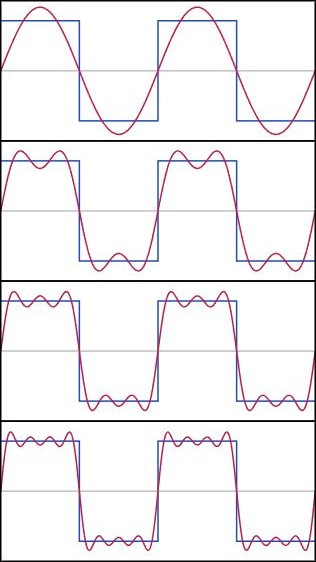

This is what’s called superposition, where the net effect of multiple periodic functions is the sum of the effects of the individual cycles. What cyclical historians like Vico and Spengler are in effect doing is running this process backward. They take a complex series that appears to be linear, and decompose it as a series of smaller wave functions in superposition.4 Where history moves in a linear fashion, very often this is a local and temporary phenomenon which then suddenly inverts dramatically. Wikipedia has a handy illustration of what this looks like:

Similarly, historical events and patterns are the sum of multiple cycles, each with its own “frequency” or period. Political cycles, economic cycles, cultural cycles, and social cycles act in concert to produce the overall shape of history, which looked at locally enough, can appear linear or chaotic. Economic cycles might interact with political cycles to produce periods of stability or instability, and the superposition of these cycles creates what appears to be historical phases or “waves” of change, even though they result from the interaction of underlying periodic factors. When economic decline coincides with political instability for example, the effects are much more pronounced, creating a significant historical event like a revolution or collapse, which seemed to come out of nowhere, but was in fact quite mechanical.

To illustrate how two periodic factors can produce a linear effect, we have plotted a measure of two factors—stability and centralization—as they were affected by major events in European history. We have split up these events into two categories—political and economic—which seem to run in cycles. So on the political side we have the Carolingian empire, the Enlightenment, and others; on the economic side we have the Black Death, the Industrial Revolution, and others. Each of these was measured in how much it fostered both stability and centralization.5 The results were illuminating.