As a public statement, we’ve made this post free to all. If you like it, please consider a paid subscription to support Imperium Press and keep us financially independent of payment processors.

If you prefer audio of this article, click here.

In this blog I try to strike a balance between depth, interest, and accessibility. If any of these suffer, it’s accessibility, though I’ve tried to give some easy entry points. This was brought home to me recently when some people expressed puzzlement over what I actually believe, particularly on liberalism. I will set this out here in plain language. Imperium, like Napoleon, seems to be a Rorschach test—to racist liberals we are Nazbols; to third-positionists we are reactionaries; to integralists and so forth we are liberals.

I am none of these things—for me all abstract principle falls away like so many dead leaves before concrete loyalty to a set of men. I call this folkishness. But if I have a political ideology, I am an absolutist.

This is why the integralist crowd projects liberalism on to Imperium—they think absolutism is a) something new, and b) something that paved the way for liberalism. Neither of these are true. We will deal with the former shortly, but you can dispel the latter by pointing out that whereas classical liberalism, Catholicism, and even identitarianism (for some) are acceptable to modern liberalism, the one thing you are not ever allowed to have is unaccountable authority, i.e. absolutism.

We should be a little more precise, because “unaccountable authority” does sound kind of terrible at first glance. The term absolute parses out to ab + solutum, or “unbound from”, and what absolute authority is not bound to are the laws. The first thing to understand is that rule of law is not, never was, and cannot ever be, a thing—not even in principle.

Rule of law is not “law and order”. It has a precise meaning—rule of law is the idea that no man is above the law. This can’t be true if you think about it for a second, because the law is a command, and a command presupposes a will. A law does not have will; only a man has will. The law cannot rule any more than a gun can kill a person—you need a man wielding it to do that. The law is no more than a tool in the hands of a man. Who is this man? In the political realm, this man is the sovereign. And it is in the nature of the sovereign to be absolute, i.e. above the law. If your sovereign is subject to the rule of law, you have simply found someone who is not the sovereign. Absolutism is not simply desirable, it is inevitable.

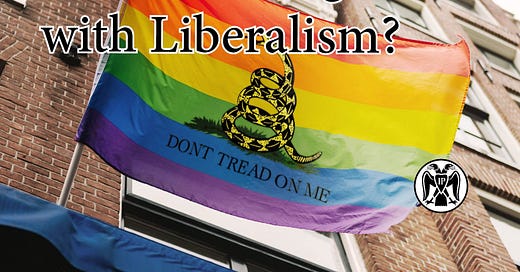

Liberalism affirms the rule of law; it is the systematic effacement of sovereignty, thus of authority. The reason why freaks, ghouls, and outsiders are allowed to run roughshod over us today is that these are all kept in check by authority, and by making all authority accountable, we have made all authority impossible.

This is not a bug that can be ironed out, but a feature, baked into liberalism from its very beginning—classical liberalism is just as poisonous as modern liberalism.1 There is no distinction to be made between them in principle, only in outcome, but we must note that modern liberalism is the logical outcome of classical liberalism, not opposed to it in any fundamental way. If the rule you followed brought you to this point, of what use was the rule?

The authority that keeps freaks in check is absolute, and at the most local level, this authority manifests itself in the authority of the father. Patriarchy has been the norm since before there were humans—it has taken classical liberalism only two centuries to dissolve it. The father is the natural head of the family, and has its interests at heart more than any other authority ever could. While the father might be subject to law outside his home, within it he is the dispenser of law and justice—this is an ancient principle called suo quisque ritu sacrificia faciat. At several levels removed, the king or duce or supreme leader occupies the same seat of authority, and like the father, his religion is the religion of the folk—this is a principle known as euis regio cuius religio, the early modern echo of the ancient principle. Nowhere is there a “right to rebellion”.

Liberalism thinks there is such a right. For liberals, the people are sovereign, meaning the king is accountable to them. And yet, the people are also subject, because they are bound by the laws, are they not? We have here a plainly incoherent idea of sovereignty, where the sovereign is also subject.

The idea that the king is above the laws is ancient. We could give many examples, but a striking one comes to us in the shape of Leonidas, the Spartan king who led the 300 against the Persians at Thermopylae. In those days, the king was also both head of the army and high priest. When the Persians marched on Greece, Sparta was in the middle of celebrating a festival, meaning that it could not march to war since the high priest had duties to fulfil. All the Spartan councils told him to stay; all the laws told him to stay; and yet Leonidas marched because his will, not the law, was decisive.2 Karl Ludwig von Haller echoes this thousands of years later when he says that the essential feature of sovereignty is independence—the king is independent of the law in his domain; the father is unbound by the law in his own home. All these are ways of saying that authority is axiomatic, primitive, and foundational.

Liberalism says that the people govern the ruler, which is the same as saying the child governs the father. Liberalism says that the law governs the man, which is the same as saying that it is the gun, and not the hood rat pulling the trigger, that is to blame. We didn’t get to where we are because liberalism was abandoned, but because it was taken to its logical conclusions.

But doesn’t “the king is above the law” negate anything like traditionalism? How can we be folkish while saying that the folk is the child and the king is the father? These were not problems for our archaic forefathers.

Recall that a law is simply a command and a command presupposes will.3 When we say that the father is sovereign within his home, this is to say that he wields the law the way Leonidas did. The will of his forefathers is decisive—he must observe the traditions—and the father must work out how to carry out their will. Invariably, as for Leonidas, different commands will at times demand opposite actions. It is here that the father acts as supreme judge, even over the laws, in determining how best to obey his forefathers’ commands. A tradition is not an algorithm that automatically spits out decision like a piece of code; it is something one defends by way of authoritative judgement. In denying the father this authority, we deny him all authority. You simply cannot have tradition without unchecked authority.

Liberalism wants to deny him this authority by making him subject to abstract principle. Going back at least as far as Kant, and with ancient roots in Plato and Zoroaster, man is no longer bound by definitive commands of his forefathers, but by universal “natural law”, meaning “no law”, because it abstracts the man from his background.

Supra-legal authority does not mean “anything goes”, but the principle of decisionism—that the king’s decision on matters of legal interpretation is final. This was known as far back as the Proto-Indo-Europeans. A cognate of the term rex (“king”) is found in the Italic, Celtic, and Vedic Indo-European branches, and by etymological analysis it becomes clear that the primitive king, far from being a merely elective princeps or “first man”,4 was the high priest who inherited an office by blood that enabled him to trace out the boundaries of towns and to set the rules of law. If we think of kingship as an extension of fatherhood and how the father is bound by the absolute authority of his own father, reconciling absolutism with traditionalism becomes totally unproblematic. In fact, without such absolute authority, tradition ceases to carry decisive force, and devolves simply to “a good idea”.

There is a meme in the dissident sphere that Europeans are aboriginally liberal, or that liberalism is “our native worldview”, or other variations on the same theme. If we think clearly about liberalism—namely as affirming rule of law, popular sovereignty, individualism, and freedom to choose one’s own path—then Europeans never were at any time proto-liberal; liberalism is not native to our psychology, and ought to be rejected. This is a learned helplessness that deradicalizes and forecloses on any possibility of fixing our problems—it is only a step away from “we wuz Greek homos” in its subversion.

Rule of law and popular sovereignty have been dealt with. As for freedom, we were never free to follow our own conscience until quite late, and where we were given some latitude (e.g. the king in matters of legal interpretation) was handed to us by our tradition. We were never free from the state, insofar as the state is the instantiation of this unaccountable authority.

To grant something to the “primitive liberalism” thesis, it’s true that in the past this unaccountable authority has been more local, authority may have ruled over a smaller horizon, but this authority was never more accountable to the ruled. At times, we were free from the distant authority of empire, but only because we were utterly subject to the local authority of the chieftain or paterfamilias. This is perhaps localism or subsidiarity, but not “individualism”—at no time did the individual have any authority over himself whatsoever.

It’s important to understand what people call “freedom” and “individualism” as distorted expressions of localism, because it makes clear that Europeans are not uniquely this way. Many other non-European peoples have similarly valued such “freedom” from distant authority such as the feudal Japanese, Turkic peoples like the Mongols, and the Joseon Koreans. If such love of local authority means liberalism, let us note that these same peoples, wherever they have suffered under modern liberalism, have deteriorated as rapidly as we have, and even faster.

Liberalism is a scourge and a blight, and the attempt to retcon it into the ancient past only mollifies and ensures defeat, and eventual ethnic death. It is disappointing to see such sentiments from, of all people, folkish pagans, since folkish paganism is precisely the opposite of liberalism, and the only real cure for it. A great part of the work done on this blog has been dedicated to examining why we have liberalism, where it came from, and when we got it, so I invite the curious to explore further.5 One thing that is clear though is that the answer is not “we have always had it because that’s how we are”. This is superficial analysis and is tantamount to saying “we deserve it”.

Throughout this article when I say liberalism, unless otherwise noted, I mean classical liberalism.

Third-positionists with a revulsion toward absolute monarchy would do well to read Carl Schmitt’s essay The Fuhrer Protects the Law, which explains this exact point. Schmitt was himself spiritually absolutist and his decisionism is absolutism’s modern expression.

He wasn’t even this among the Germanics, whose supposedly elective kingship is often cited as evidence of primitive liberalism.

See especially those articles in the Guide under the headings “The Axial Roots of Modern Decline”, “Propositionality”, and “Imperative Ethics” in that order.

Interesting. I was caught in what I call the loop of liberalism. That loop is that you accept that we all must have fealty to the ideas. The system isn't working and so instead of exiting you stay in the loop. The first re-entry is studying more and getting better at explaining the ideas as you understand them better. The next re-entry is evangelizing the ideas. If they only understand them properly, they will behave optimally in accordance with the ideas. The next re-entry is becoming the "ownster." An ownster is the person who thinks himself so clever as he owns the libs by repeating the most obvious and inane of memes and critiques. He holds the high ground, surrounded, more badly outnumbered, more perilously besieged at twilight with every own.

'See', he says. 'You are a hypocrite. You are not adhering to the ideas.' He is trapped. The idea is sacrosanct, and so he cows himself by refusing to give up on the ideals his enemies have put into his head. He embraces the purity of self-defeat. He looks to the right at those who have exited the loop. "You sound just like them", he says with scorn and spite. He is like a pacifist whose village and people will burn refusing to take up arms, all to adhere to an idea that says it is a sin to mount an effective defense. He does this even as reality hits him with the full force of the savage and brutal contempt it holds for those who lack the will to survive. The loop of liberalism is fatal.

Leonidas halted the rites so he and his people would live to perform them another day.

Great post, a lot to think about.

The question in my mind is how we handle, e.g., an absolute leader who rejects or dishonors the folk/volksgeist. We are always left asking (asking OURSELVES! of course) how to answer this, which, as you say, is a problem, that reversion to personal preference and liberal principles. But does power always determine folk, no matter how twisted or seemingly deranged?

I would like to think that all the thoughts in our minds are not necessarily our own, and that a people can know what its volksgeist demands, a sort of collective folk-consciousness, and that this is not necessarily populism or liberalism. But how is the nature of a people determined, by voting? Lol

I’m in a loop on this one.