If you prefer this article in audio click here.

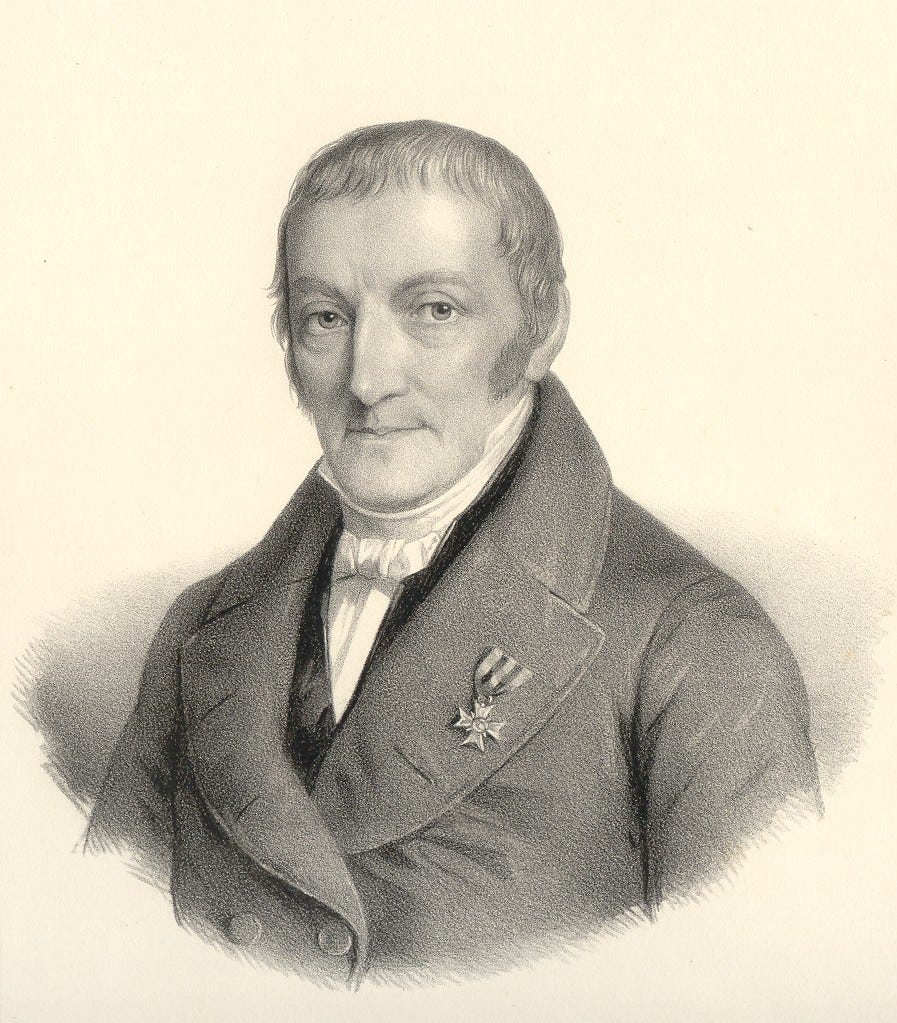

Karl Ludwig von Haller is one of the strongest Counter-Enlightenment voices and yet has remained inaccessible to the English-speaking world for two centuries until we published him last month. In this article we will unpack his thought and explain why he matters to us today, which he absolutely does, maybe even more than a Maistre or a Filmer. You can buy the book here:

Many people have asked me in private what Haller is all about. Beyond all the theory, the core of his work is quite simple: great man, you deserve to be where you are—don’t think you have to be accountable to anyone but God.

This is a good message—Haller is exhorting what we have called the Odinic man, the founder. Some of you will be troubled by this though, wondering if an unaccountable Caesar really is what we need. But there’s a greater threat looming than a rex, and anyone more worried about a king than what we have is utterly useless.

What we call “Our Democracy” is not a tyranny. It’s a ship adrift at sea with nobody at the helm, filled with a bunch of gangsters trying to loot what’s left of it as it slowly subsides into the deep, taking all of us down with it. The problem isn’t a tyrannical captain, the problem is no captain. Final responsibility, ownership, and control are concentrated in nobody at all, but distributed across a vast oligarchy of criminals engaged in civil war, both against each other and against the people they “govern”. This situation is terminal. Enter Haller.

The ideal person to read Haller would be someone like Elon Musk. Say what you will about Musk,1 he is a man of energy and means. Haller basically says to him “you should be a law unto yourself”. Because the centre of our social order has collapsed, in the coming decades various competing centres are going to emerge as the order devolves to more localized levels. This has happened many times before: as empire crumbles, we get warlordism. If great men think about this now, take it seriously, and engage in something like folkbuilding, there will be nodes of power left after the whole thing comes down. And not just nodes of power, but centres of real culture with a considered moral foundation and worldview, not just “the right of the stronger” for its own sake.

Haller wrote his Restoration of Political Science in six volumes, the first of which Imperium Press has now published. This first volume lays out his patrimonialist system, refutes many liberal theorists, and shows how his system is superior to theirs. The remaining volumes show how patrimonialism applies to various kinds of states: monarchies, republics, military dictatorships, and ecclesiastical states. In the first volume, he demonstrates that the French Revolution failed to bring about a liberal republic but rather anarchy, and could only be righted by the exact opposite of liberalism: the absolute personal rule of Napoleon. It is this absolute personal rule of the strongman that Haller champions, where private law is the only law,2 and where political authority and legitimacy are functions of the sovereign’s power. The kernel of his thought runs thus:

In short, whenever a man makes himself useful or indispensable to others, whenever he can save them from some evil or procure them some good, he rules over them and makes their laws.3

Haller was not the first to observe this. Rule of the stronger has been known since the dawn of time in every culture—it is the default state of human sociality. Others, including Haller’s own grandfather, articulated it in the modern era but Haller added to power the function of independence to complete the system.4 What distinguishes the sovereign from others with power such as fathers, chieftains, military leaders etc. is total independence, with no one above them to check them. This is strikingly similar to absolutist conceptions of sovereignty—we will return to this later.

To emphasize this point, Haller says that “all States are nothing more than republics by another name, and the private thing of the prince becomes a public thing”, and by this he means not the modern idea of a limited republic, but the res publica of the Roman state, the “public thing” that all partake in, but only some—ultimately, one—actually has right over. This makes elective and delegative monarchy totally impossible, and the same is true a fortiori of democracy. Speaking about his discovery of this principle, he says:

In short, there was nothing the personal right of princes couldn’t explain in an illuminating way, no question whose natural answer it couldn’t furnish. Everything from the origin, legitimate exercise, heritability or transfer, and decadence of sovereign power to the means of strengthening it can be derived from personal right in the most elegant and satisfactory way.5

All this talk about power and the right of the stronger makes Haller sound like a Nietzschean, and taken out of context he could be mistaken for one.6 He has an answer for this:

For example, many men seem to believe that, in my theory, I did nothing but establish the right of the strongest. Certainly, that wouldn’t have been much of a discovery. All authority very much needs to be founded on some kind of power: the question boils down only to whether this power is personal or delegated, and for my own part, I can’t conceive of how there could be more abuse to fear from the first than the second.7

Rule of the stronger is not just “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must”—God, or perhaps today we would say nature, has arranged things this way in order to benefit the weaker:

It is precisely in order to make abuse less common, in order that there should be less injustice and violence on Earth, that nature has remitted power to the most powerful. For, in order to do good, it isn’t enough to know and to wish; power is needed above all.8

The characteristic of any asymmetrical relationship—husband and wife, doctor and sick, lawyer and client, master and apprentice—is the greater power or natural superiority in the one, and in the other the need for nourishment, protection, instruction, or direction that this power satisfies. This is not power for its own sake, but power in the service of the relationship as a whole. No less for the king and his subjects or the lord and his retainers.

Liberals, the enemies of authority, have cooked up the idea of primitive man as existing before any such relationships, in a pre-social world of atomic individuals rattling around the steppe or the jungle. Hobbes and Rousseau come in for a particularly severe beating here, but they are not the originators of this nonsensical doctrine. Haller locates the root of “man as independent of or prior to his tradition” in the attempt to copy/paste Roman law on to Germanic custom in the Middle Ages. Roman law fits poorly with this custom and has little non-republican terminology, so this enabled the enemies of tradition to shoehorn foreign and inappropriate concepts into the tradition as though they were aboriginal to it. The result was what we have come to know as “social contract theory”, which answers to no historical reality at all. Haller administers such a savage beat down to social contract theory that at times it becomes laugh-out-loud funny:

[These theorists] distinguish between the historical origin of States and what they call their juridical origin, that is to say, an historically false origin, asserting with singular arrogance that, even though no State was ever the product of a social contract, they nonetheless could have or should have formed this way. [...] Until now, fathers doubtlessly had children, and that’s their historical origin; but according to their juridical origin, the children should have had their father. The boss gives orders to his workers, because he was there before they were, and took them into his service, and that’s the historical origin of his workforce; but according to its juridical origin, the employees should be boss, and the boss the employee; and this is what they call reason, even though it contradicts the first rule of reason, which holds a thing cannot be and not be at the same time. Trees have all their roots in the ground and branches in the air, that’s the fact; but according to the rationalist conception, the branches should have been in the ground and the roots in the air, or at least philosopher-gardeners should try to bring trees into as close an approximation as possible to this most rational ideal.9

Thus far Haller seems like an arch-reactionary in the vein of a Hamann or a Maistre, but at times he seems to verge on what we would now call libertarianism. While libertarianism is foundationally flawed, nobody wants a “totalitarian” ruler micromanaging every aspect of life. Nor does Haller:

None of these superiors received his being and his power from his subordinates, but holds each of them as gifts of nature, that is to say, by the grace of God; they are innate to him, one might say, or better still, acquired as a result of something innate. The subordinates, for their part, made no sacrifice of their liberty, nor any existing right; they naturally find themselves dependent, or better still voluntarily entered their master’s service, not in order to become more free (which would entail a contradiction), but to satisfy their needs, to be fed, protected, educated, and secure an easier and better life for themselves. […] Each of them contracts according to his own understanding of what his needs are and what he seeks to accomplish, with the sole exception of universal Divine law, from which nobody is exempt. Here everything is free, natural, and without coercion. There is no unjust coercion in a man’s entry into social relations, nor in the period of their duration, or the time when he leaves them; they can dissolve, and the two parties have the ability to renounce an individual contract.10

One wonders what there is in Hoppe that is not already in Haller. Absolute personal rule is not incompatible with freedom—the patrimonial sovereign will of course delegate responsibilities, but unlike in a democracy where no one is accountable, he is ultimately responsible for the outcomes of his delegates’ decisions. This is one of the great strengths of absolutism, and Moldbug is right to point out that a strong sovereign is a small-government sovereign.11 Absolute power does not corrupt absolutely, quite the reverse. Unlike in democracy, in the patrimonial state everyone knows who’s in charge, so the ruler is more and not less likely to have his subjects’ interests at heart. When Haller says that princes govern not the affairs of others, only their own,12 he is basically echoing what neoreactionaries two centuries later would call “no voice, free exit”.

There’s a tension in Haller between his defense of freedom on the one hand, and of supreme power and dependence on the other, that never quite gets resolved. Much like with Filmer, who has a tension of his own,13 rather than being a weakness this is what makes him interesting and fruitful. And also like Filmer, he affirms the basic insight of absolutism: sovereignty is conserved, in other words, someone always occupies the centre, the position of supreme and legally unconstrained authority, who is accountable only to God. Any attempt to clarify, formalize, and manifest this authority can only benefit society; any attempt to efface, conceal, or do away with it can only end in disaster. In a passage that could have been taken from the pages of Filmer’s Patriarcha, we are told:

Fill human associations with as many written laws, constitutions, and structures as you like; dismember their power, or use what you call checks and balances in order to maintain their equilibrium; at most you’ll alleviate the problem, but you’ll never be able to destroy the law of nature: some individual or body will always be the most powerful, and wield supreme authority; and abuse becomes possible just as soon as there exists power and will enough to commit it. Constitutions and structures are then brought down, checks and balances set aside, and human laws respected even less than Divine law. Alternately, if some supposedly supreme power finds itself excessively restrained by an opposing power; if there are constant struggles between them; neither of them can provide protection any longer; one force is paralyzed by the other; and then everybody sees themselves once again exposed to all manner of abuse by private power, or a foreign and belligerent power. History furnishes more than enough cautionary tales of this truth. The strongest always ends up ruling; but this time also has a greater interest in oppressing, as well as greater means of doing so. The new state of affairs is usually worse than the old; peoples go from cough to cold, from frying-pan into fire; they tear out the hedge, and get bitten by the snake.14

Haller’s conception of the social order is strong meat even for the radical right, perhaps too strong for most. He bulldozes ideas cherished even in our circles—such as popular sovereignty, primitive Germanic liberalism, and the general will—as so much sentimental cant and ahistorical dilettantism. This is a cold shower, but a much needed one.

There is, however, a more serious question about his uses for a revitalized right that wishes to push over a tottering and hostile regime. Haller’s defense of authority is anti-revolutionary in the extreme. It would have been useful in its actual historical context: in the hands of a sovereign restored after the French Revolution. But now that the “strongest”, “most independent” men today are people like Larry Fink and George Soros, is it perhaps positively harmful? Does this make it the enemy of the radical right?

This can be sustained only on a superficial reading of Haller. He himself has throughout his book demonstrated that Fink and Soros are the inevitable result of checks and balances, popular sovereignty, and a “limited” executive. Because of this, “it will take a usurper still more terrible than Napoleon, before peace can be restored to our wish”, and with every passing day we are more inclined to believe him. Haller’s unique value lies in telling the Napoleon of the 21st century that his will is valid, his command sovereign, and his destiny our destiny. The Weltgeist may not ride in today on horseback with a sword, but wielding blockchain, encryption, and a vast army of managers ready to deal a fatal blow to the system using 5G warfare rather than 1G. Haller is no less valuable to this Weltgeist for all that, and the best use of him can probably be made by tech barons and the like.

He looked back on the French Revolution with a penetrating gaze and saw that it went in the only direction it could go, until a great man once again held sway with absolute rule. Above even those great men to whom Haller addresses himself, he should be read by those who doubt “great man theory”, which for the first several millennia of the human endeavour was just called “history”, and who think that we can save ourselves by spontaneous, bottom-up self-organization. He wrote about the French Revolution, but he might as well have been writing about today:

In spite of false principles and written constitutions, it was necessarily the case that there would obtain a power superior to the others; or rather, when there existed equality of forces and opposing interests, everything inevitably had to be decided by war, a fight to the death that once again secured exclusive rule for the strongest. [...] Thus an attempt was made at doing violence to nature; but her indestructible laws only took another course, one that was disastrous; and the foolhardy endeavour of men was chastised by unheard-of calamities. In the end, it is always the strong who rule; but instead of a natural power, legitimate in its origin and exercise, provident for the needs of others, and as such even benevolent, there arose illegitimately-acquired violence, contrary to nature, lawless and unbridled in its exercise, itself exposed to need, hence tyrannical for its satisfaction, and whose end everybody looks forward to with impatience.15

At the risk of stating the obvious, I am not calling Musk “our guy”.

Private law being the will of the absolute sovereign.

Karl Ludwig von Haller, Restoration of Political Science, vol. I (Imperium Press, 2023), p. 177

Ibid, p. 142.

Ibid. p. liii.

Cf. the passage on p. 176 (ibid.) “Consider the animals of the field…”

Ibid. pp. lxiii–lxiv

Ibid. pp. 182–183.

Ibid. p. 144 and note.

Ibid. pp. 170–171.

For more on this, see Nicholas Henshall, The Myth of Absolutism.

Haller, Restoration vol. I, p. 251.

Between Protestantism and subjection.

Haller, Restoration vol. I, pp. 212–213.

Ibid. pp. 129–130.