If the flowering tree crown wanted to analytically examine its root, it would pay for it with its life.

Houston Stewart Chamberlain, 1905

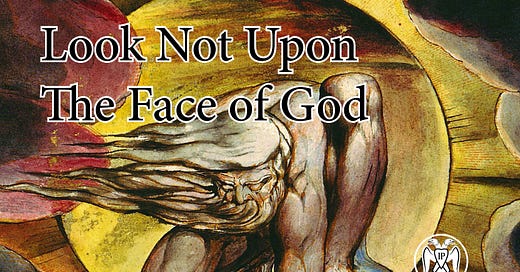

One of the important lessons of the Counter-Enlightenment—from Vico to Maistre and beyond—is that there are some things you don’t get to question. This is why at the end of the day Socrates got what he deserved: even in Periclean Greece, already far degraded and desacralized from its Mycenaean origins, the Greeks saw him as a corrosive and irreligious figure. The prohibition not to look on the face of God, not to invoke Khaos, not to inquire into the arche of the world, is near universal among human communities. Reason must be circumscribed, must be limited in its scope and application, and if you ask too many questions about why, you get the hemlock. This is tradition. Many of you are not quite ready for it.

Socrates was the harbinger of the end for Greece; when you see him, you are not surprised to find Greece a Roman vassal just a couple of centuries later. And so it is with philosophy more generally—when you see the medieval scholastics you are not surprised to see the Reformation, Jesuitism, Bellarmine and Suarez, and liberalism, within a few centuries. We could produce examples in India, China, Egypt, and among the Aztecs. This is something of a historical law: philosophy ebbs in a people’s youth, flows in its old age.